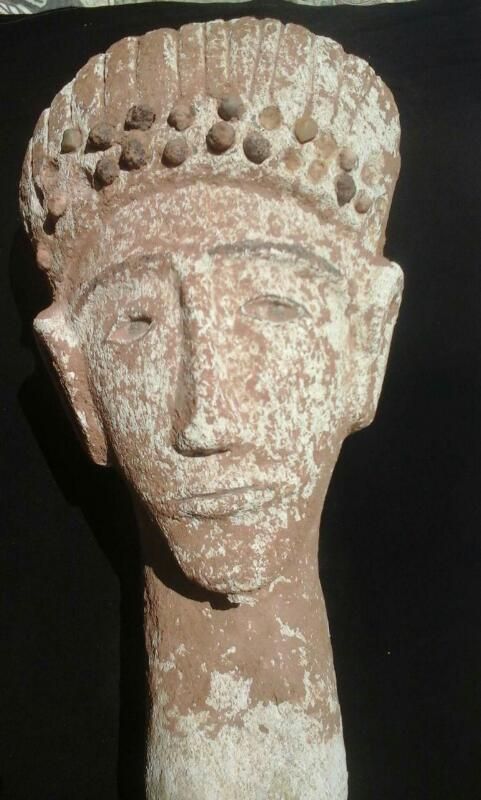

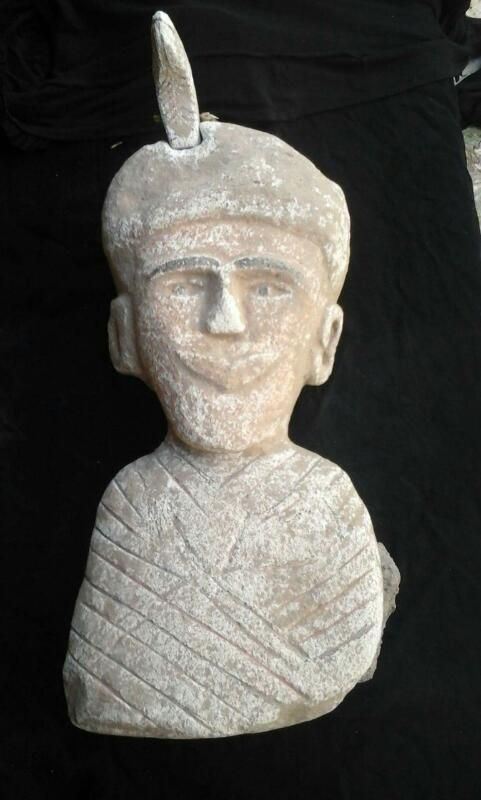

A farmer reportedly found these sculptures on his land in the hills above Berbera, and I secured them for future research. I have pledged to keep them in Somaliland and accessible to experts, although for the time being I have not decided to which institution I will give them. When the municipality of Berbera opens a planned museum and the conditions there are considered appropriate for conservation, safety and display, they can go there; in the meanwhile a university in Hargeisa may be entrusted with their care.

Images of these sculptures and inscriptions had been circulating in Somaliland on whatsapp looking for a buyer. The first time I saw them was in Berbera, and they had so intrigued me that I shared them with experts who were as puzzled as I was. Stylistically, they are unlike any other known. There is no record of similar finds in the Horn of Africa. I had even written to Graham Hancock, one of the leading experts on lost civilisations. He encouraged me to do further research but then my other occupations engulfed me.

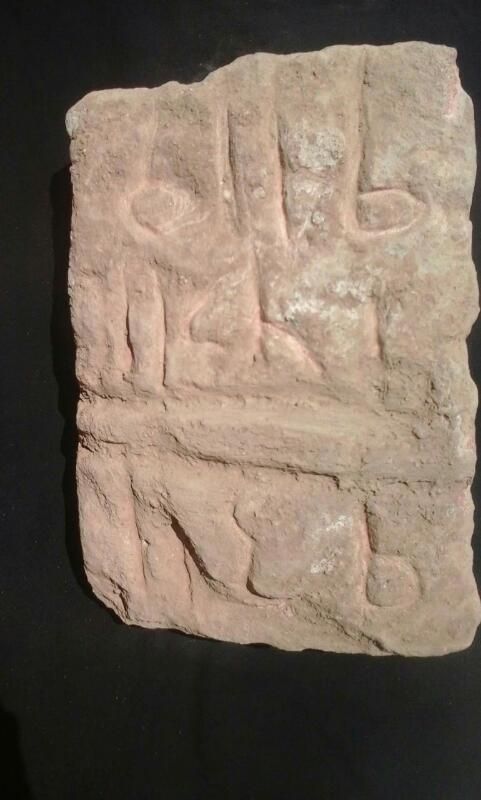

The second time I encountered these images, I asked if I could see them. Someone agreed to bring them to me. After careful examination I came to the conclusion they are genuine. Although I am not an academic expert on cultural heritage, I have been professionally involved in discerning fake ancient artefacts. These statues and inscriptions, I believe, are roughly two thousand years old; say from the second century AD.

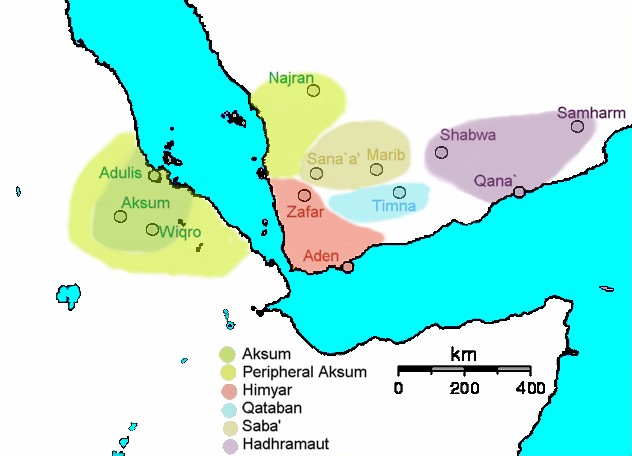

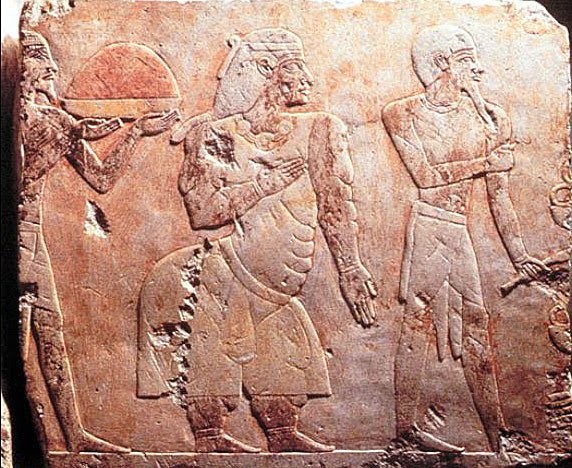

At that time the region was prosperous. The Kingdom of Axum along the southern shores of the Red Sea, and in Yemen the Himyarite Kingdom, Hadramawt, Qataban and the Sabaeans counted among the more developed cultures of their age. The ‘Periplus of the Erythraean Sea‘, dated to approximately 50 CE, describes the ports along the coast of Berbera (now Somaliland and Puntland) with sufficient detail to positively identify the major port of Malao with present-day Berbera. About Malao, the author writes “Here the natives are more peaceable. There are imported into this place the things already mentioned [i.e. gold, silver, iron], and many tunics, cloaks from Arsinoe, dressed and dyed; drinking-cups, sheets of soft copper in small quantity, iron, and gold and silver coin, not much. There are exported from these places myrrh, a little frankincense, (that known as far-side), the harder cinnamon, duaca, Indian copal and macir, which are imported into Arabia; and slaves, but rarely.” In and around Berbera ample evidence of ancient occupation has reportedly been dug up, including cemeteries where people are not buried in the Muslim way, artefacts and traces of ancient buildings.

The seven objects portrayed above are those I secured. I have seen images of other markedly similar statues and inscriptions. There are really three groups of objects here: the ‘whitish’ (maybe limestone) statues, the ‘reddish’ (maybe sandstone) statues, and inscriptions. The former are figurative, and have human character traits; the second group tends towards abstraction. I have not found out yet in which script the text is, but it seems some kind of proto-Arabic.

A more detailed report of my examination can be downloaded here.

None of this is familiar. As connoisseurs of Yemeni art pointed out, these statues do not belong to one of the known styles that proliferated in this period. For a gallery of some stunning works of ancient Yemeni art, see the the Museum of Contemporary Ancient Arabia. They do not point to Axum either, although much less is known of ancient Axumite art.

It would be one thing to find a cache of statues procured by trade, but it is quite another if no obvious cultural paternity can be found for them. They have either been produced locally or brought in from other areas outside the known historic world. In both cases, such a find suggests Somalia’s history should be rewritten.

The official narrative among Somalis is that they descend from Arab paternity and African maternity. Their forefathers were illustrious sheikhs who emigrated from the Gulf countries in the earliest wave of the spread of Islam, and married the daughters of local nomads, giving rise to the clan groups which still dominate Somali society today. Thus originated, the Somali clans slowly spread southward from the coast of the Gulf of Aden.

The existence of a Somali culture prior to Islam is ignored in this narrative, as all culture would have come with the new religion; but research by Somali scholars has unearthed a much older substratum. Approaching the subject from a variety of perspectives, including folklore, language, psychology and genetics, it appears a strong local culture evolved much earlier than Islam in the Horn of Africa. This includes a clearly defined belief system before Islam – see the groundbreaking work by Professor Bulhan. However, until now few material remains have been found from this period, although rock paintings found at Laas Geel and other sites show that the region was inhabited by fairly advanced artists four to five thousand years ago.

This discovery, if indeed it points to a flourishing local culture, sufficiently developed to either produce or collect such statues in pre-Islamic times, could have a significant impact in the current search for a Somaliland identity. It is now plagued by its clanic nature, which ensures some population groups feel more entitled to the Somaliland identity than others. In 27 years of de facto independence, a certain ‘Somalilander’ identity is being formed anyhow, above and beyond clan lineage. A link to a ‘pre-clan’ past could be most opportune in the process of national identity formation.

I have traveled a bit through Somaliland, and have often imagined seeing ancient cities or forts in tumuli. The flora and fauna was certainly more diverse, and apparently the climate more humid in the past. Somaliland shared with Yemen a very precious resource, namely frankincense, of which the Romans were avid consumers. Before that, Egyptian chronicles of the 23rd and 15th centuries BC refer to trade with the Land of Punt (most probably the Horn of Africa/Puntland) and to its Queen Ati, displayed on the mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut with African curves. The Berbera coast’s location on the trade routes from the Red Sea to East Africa and the Indian Ocean must have been beneficial. In other words, it would stand to reason that this coast indeed flourished (at times) in antiquity.

Gradually, new archaeological discoveries in East Africa are indicating that this region has been long integrated in the ‘antique’ world, and not only by trading posts of external cultures, but by inland African cultures that flourished and then often disappeared without much trace. This contradicts still prevalent stereotypes about the lack of historical development in Africa and its undeveloped inhabitants, ‘noble savages’ at best. Somalis, as argued by Professor Bulhan, suffer from this inferior self-image.

The current state of Somaliland has not yet demonstrated much interest in or capacity for cultural heritage or its preservation, but individuals and ‘civil society’ groups I met are very motivated to uncover and interpret this past. The Berbera municipality has already self-financed a public library, now they also have plans to restore a British colonial building to house a museum. I greatly encourage international specialists and researchers to engage these people and groups, and assist Somaliland in this effort.

One need not be deterred by security concerns: there hasn’t been a terrorist attack in ten years; Somaliland, in particular the area around Berbera, has been one of the safest of the region.

Queen Ati’s ”curves” are most likely from some sort of disease. It doesn’t look natural nor typical for Somalis. Scholars who researched these paintings seem to think the same.

A very interesting document,I hope the new Berbera Museum is deemed to be the best place for these artifacts to be housed.I am in possession of an artifact? That should be returned to the museum ( my old house) it’s the hughes drill bit used to drill the final few feet of the first well drilled by B.P.Exploration 1959/60.

At present it is safely stored away at my home in England.

Thank you Barry. I drove through Berbera recently, and the authorities are busy repairing one of the old British colonial buildings to house the future museum. They’re serious about it and not waiting for external funding. Let’s see if I can find a picture

Good work securing them Robert. And i loved your detailed breakdown and examination of these artifacts in your document.

Are you aware that there has been found similar artifacts in Gol Waraabe?. One of the sculptures you have shown particularly the Prince shares remarkable resemblance to the sculpture on the front cover of this book: https://www.amazon.com/Mystery-Land-Punt-Unravelled/dp/8799520826

I was a bit sceptical about their authenticity at first but after looking at your document there can be no doubt they are real. They are eroded and possibly part of this mysterious Ancient Punt civilization. Do you know if any archeologists or experts have reached out to have them carbon dated yet? or shown interest?

Dear Hangool/Steve Bohizer

Actually I recently had the chance to see the (very small) collection of Somaliland’s Department of Archaeology, and there were four more statues looking very similar. This made me suspicious, and I really can’t affirm any more that they must be authentic, as I did in this post. I’m withholding judgment. Either there’s a very expert falsifier who is intelligently spreading the statues (because those at the Department were not paid for) or else there is a temple or other excavation site where many of these statues were found. They really need to be expertised soon!

Thanks for the Gol Waraabe tip, and let’s stay in touch (I can be reached at robertkluijver at gmail

I am not sure if there is an expert falsifier behind them, but those artifacts housed at the Department may have either have been dug up seperately and donated by Ahmed Ibrahim Awale.

But i suspect that the Somaliland authorities and the people there are trying their best to keep these artifacts under wrap for protection from looters until they establish it with better security and funding for it. Then they will make them available to experts later on i persume.

If you are interested i think you should contact Awale . According to his foundation website he can be reached at Aiawaleh at gmail. He has been on the news related to Somaliland biodiversity discoveries. He can tell you more about them and the excavation site at Gol Waraabe.

Thank you Hangool for the tip. That’s great and I’m so sorry that I hadn’t paid attention to it until now! I will get in touch with Awale.

Pingback: The Mystery of the Land of Punt Unravelled – book review | Land of Punt

can I ask how you determined these artifacts are indeed ancient and at least 2000 thousand years old?

Hi Jama, as I write in my blog, I am not sure of it, but I’m inclined to believe the artifacts are old. I examined the pieces carefully and I couldn’t find any sharp edges or anything that indicates newness. I saw very faint traces of paints with natural hues on one of the statues. I also noticed that somebody had tried to fix one of the statues crudely, using superglue to fix stones to a crown-like headdress. A counterfeiter would not have done this, ruining the value of his own work. There was also a refined aesthetic to several of the limestone (white) statues, which one rarely finds on fakes. There are also circumstantial reasons, including the lack of a market to cater to (there is no interest in ‘Somali antiques’ as nobody has ever heard about them); the lack of these kind of counterfeiting skills in Somalia; and the invitation of the finder of the pieces to take me along and show me where they were found.

But I must admit that when I saw similar statues in the museum depot in Hargeisa, I also started doubting their authenticity.

It needs more research but I wouldn’t dismiss them out of hand as being fakes.

Best, Robert

Queen Ati curves are not from a disease , her curves are what is natural for subsaharan people, we see similar depictions like this of Nubian queens. This is evident , so evident that the people who found the images of queen Ati tried to remove it.

Pingback: The Mystery of the Land of Punt Unravelled – book review | Land of Punt